In Decisive, Chip Heath and Dan Heath, the bestselling authors of Made to Stick and Switch, tackle the thorny problem of how to overcome our natural biases and irrational thinking to make better decisions, about our work, lives, companies and careers.

When

it comes to decision making, our brains are flawed instruments. But given

that we are biologically hard-wired to act foolishly and behave irrationally at

times, how can we do better? A number of recent bestsellers have

identified how irrational our decision making can be. But being aware of a

bias doesn't correct it, just as knowing that you are nearsighted doesn't help

you to see better. In Decisive, the Heath brothers, draw on extensive

studies and stories...

The

Four Villains of Decision Making

Steve

Cole, the VP of research and development at HopeLab, a nonprofit that fights to

improve kids’ health using technology, said, “Any time in life you’re tempted

to think, ‘Should I do this OR that?’ instead, ask yourself, ‘Is there a way I

can do this AND that?’ It’s surprisingly frequent that it’s feasible to do both

things.”

Cole

is fighting the first villain of decision making, narrow framing, which

is the tendency to define our choices too narrowly, to see them in binary terms.

We ask, “Should I break up with my partner or not?” instead of “What are the

ways I could make this relationship better?” We ask ourselves, “Should I buy a

new car or not?” instead of “What’s the best way I could spend some money to

make my family better off?”

Our

normal habit in life is to develop a quick belief about a situation and then

seek out information that bolsters our belief. And that problematic habit,

called the “confirmation bias,” is the second villain of decision

making.

And

this is what’s slightly terrifying about the confirmation bias: When we want

something to be true, we will spotlight the things that support it, and then,

when we draw conclusions from those spotlighted scenes, we’ll congratulate

ourselves on a reasoned decision. Oops.

The

third villain of decision making: short-term emotion. When we’ve got a

difficult decision to make, our feelings churn. We replay the same arguments in

our head. We agonize about our circumstances. We change our minds from day represented

on a spreadsheet, none of the numbers would be changing—there’s no new

information being added—but it doesn’t feel that way in our heads. We have

kicked up so much dust that we can’t see the way forward. In those moments,

what we need most is perspective.

The

fourth villain of decision making is overconfidence. People think they

know more than they do about how the future will unfold.

If

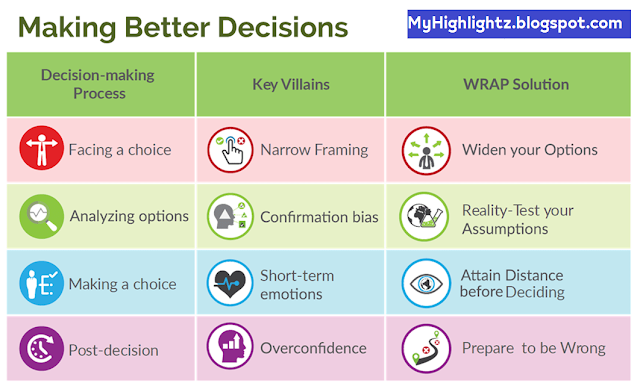

you think about a normal decision process, it usually proceeds in four steps:

• You encounter a choice.

• You analyze your options.

• You make a choice.

•

Then you live with it.

And

what we’ve seen is that there is a villain that afflicts each of these stages:

•

You encounter a choice. But narrow framing makes you miss options.

•

You analyze your options. But the confirmation bias leads you to gather

self-serving information.

•

You make a choice. But short-term emotion will often tempt you to make the

wrong one.

•

Then you live with it. But you’ll often be overconfident about how the future

will unfold.

So,

at this point, we know what we’re up against. We know the four top villains of

decision making. We also know that the classic pros-and-cons approach is not

well suited to fighting these villains; in fact, it doesn’t meaningfully

counteract any of them.

Now

we can turn our attention to a more optimistic question: What’s a process that

will help us overcome these villains and make better choices?

You

encounter a choice. But narrow framing makes you miss options. So …

→

Widen Your Options.

You

analyze your options. But the confirmation bias leads you to gather

self-serving info. So …

→

Reality-Test Your Assumptions.

You

make a choice. But short-term emotion will often tempt you to make the wrong

one. So …

→

Attain Distance Before Deciding.

Then

you live with it. But you’ll often be overconfident about how the future will

unfold. So …

→

Prepare to Be Wrong.

Avoid a Narrow Frame

“Widen

Your Options.” Can we learn to escape a narrow frame and discover better

options for ourselves?

The

first step toward that goal is to learn to distrust “whether or not” decisions.

In fact, we hope when you see or hear that phrase, a little alarm bell will go

off in your head, reminding you to consider whether you’re stuck in a narrow

frame.

If

you’re willing to invest some effort in a broader search, you’ll usually find

that your options are more plentiful than you initially think.

You

won’t think up additional alternatives if you aren’t aware you’re neglecting

them. Often you simply won’t recognize you’re stuck in a narrow frame.

Focusing

is great for analyzing alternatives but terrible for spotting them.

What

if we started every decision by asking some simple questions: What are we

giving up by making this choice? What else could we do with the same time and

money?

Vanishing Options Test, which you can adapt to your situation: You cannot choose any of the current options you’re considering. What else could you do?

The

old saying “Necessity is the mother of invention” seems to apply here. Until we

are forced to dig up a new option, we’re likely to stay fixated on the ones we

already have. So our eccentric genie, who seems at first glance to be

cruel—he’s taking away our options!—may actually be kindhearted. Removing

options can in fact do people a favor, because it makes them notice that

they’re stuck on one small patch of a wide landscape. (Of course, we should be

clear that people respond much more cheerfully when you metaphorically, rather

than literally, remove their options.)

Multitrack

Nothing

ventured, nothing gained.

When

life offers us a “this or that” choice, we should have the gall to ask whether

the right answer might be “both.”

If

people on your team disagree about the options, you have real options.

Find

Someone Who’s Solved Your Problem

1.

When you need more options but feel stuck, look for someone who’s solved your

problem.

2.

Look outside: competitive analysis, benchmarking, best practices.

3.

Look inside. Find your bright spots.

4.

Note: To be proactive, encode your greatest hits in a decision “playlist.”

•

A checklist stops people from making an error; a playlist stimulates new ideas.

•

Advertisers Hughes and Johnson use a playlist to spark lots of creative ideas

quickly.

•

A playlist for budget cuts might include a prompt to switch between the

prevention and promotion mindsets: Can you cut more here to invest more there?

Zoom

Out, Zoom In

Zooming

out and zooming in gives us a more realistic perspective on ourchoices. We

downplay the overly optimistic pictures we tend to paint inside our minds and

instead redirect our attention to the outside world, viewing it in wide-angle

and then in close-up.

Ooch

To

ooch is to construct small experiments to test one’s hypothesis. (We learned

the word “ooch” from NI, but apparently it’s common in parts of the South.

Maybe it’s a blend of “inch” and “scoot”?) Hanks said, “Part of the culture

here is to ask ourselves, ‘How do we ooch into this?’ … We always

ooch before we leap.

That

diva-ish, “I just know in my gut” attitude is inside all of us. We won’t want

to bother with ooching, because we think we know how things will unfold. And to

be fair, if we truly are good at predicting the future, then ooching is indeed

a waste of time.

So

the key question is: How good are we at prediction?

To

the extent that we can control the future, we do not need to predict it.”

To

ooch is to ask, Why predict something we can test? Why guess when we can know?

Those questions bring us to the end of this section, in which we’ve been

studying strategies for fighting the confirmation bias. The basic problem we

face, in analyzing our options, is the right kinds of information: zooming out

to find base rates, which summarize the experiences of others, and zooming in

to get a more nuanced impression of reality. And finally, the ultimate

reality-testing is to ooch: to take our options for a spin before we commit.

We

will usually have an inkling of the one that we want to be the winner, and even

the faintest inkling will propel us to gather supportive information—and

sometimes nothing but supportive information. We cook the books to support our

gut instincts.

Overcome Short-Term Emotion

My

friend, the feel of the wheel will seal the deal.

We

are not slaves to our emotions. Visceral emotion fades. That’s why the folk

wisdom advises that when we’ve got an important decision to make, we should

sleep on it. It’s sound advice, and we should take it to heart. For many

decisions, though, sleep isn’t enough. We need strategy.

There’s

a tool we can use to accomplish this emotion sorting, one invented by Suzy

Welch, a business writer for publications such as Bloomberg Businessweek and O

magazine. It’s called 10/10/10, and Welch describes it in a book of the same

name. To use 10/10/10, we think about our decisions on three different time

frames: How will we feel about it 10 minutes from now? How about 10 months from

now? How about 10 years from now?

To

be clear, short-term emotion isn’t always the enemy. (In the face of an

injustice, it may be appropriate to act on outrage.) Conducting a 10/10/10

analysis doesn’t presuppose that the long-term perspective is the right one. It

simply ensures that short-term emotion isn’t the only voice at the table.

Perhaps

the most powerful question for resolving personal decisions is “What would I

tell my best friend to do in this situation?

Honor

Your Core Priorities

You

know how after you ride a roller coaster, they try to sell you a photo of you

shrieking during the ride? You might impulsively buy the photo because you’re

flush with adrenaline. “But the next day,” she said, “do you really want that

picture? Not really. No one looks good on a roller coaster.”

When

we identify and enshrine our priorities, our decisions are more consistent and

less agonizing.

Every

day, all of us struggle to stay off List B and get back to List A. It’s not

easy. Remember that MIT study showing that, over the course of a week, managers

spent no time whatsoever on their core priorities? Peter Bregman, a

productivity guru and blogger for the Harvard Business Review, recommends a

simple trick for dodging this fate. He advises us to set a timer that goes off

once every hour, and when it beeps, we should ask ourselves, “Am I doing what I

most need to be doing right now?

He

calls this a “productive interruption,” one that reminds us of our priorities

and aspirations. It spurs us to get back to List A.

Bookend

the Future

The

future isn’t a point; it’s a range: Even when we can’t minimize bad outcomes,

we still do ourselves a favor.

It’s

easier to cope with setbacks when we’re mentally prepared for them.

Stacking

the deck makes us more likely to succeed, but even with the best forethought

and planning, sometimes things don’t go well.

Trusting

the Process

Success

requires two stages: first the decision and then the implementation.

When

you can articulate someone’s point of view better than they can, it’s de facto

proof that you are really listening.

The same goes for defending a decision. If you’ve made a decision that had some opposition, those opponents need to know that you haven’t made the decision blindly or naively. Our first instinct, when challenged, is usually to dig in further and passionately defend our position. Surprisingly, though, sometimes the opposite can be more effective.

“Sometimes

the best way to defend a decision is to point out its flaws.”

We can’t know when we make a choice whether it will be successful. Success emerges from the quality of the decisions we make and the quantity of luck we receive. We can’t control luck. But we can control the way we make choices.

No comments:

Post a Comment